|

|

“And here’s the birthday party—had to honor the

birthday parties... This is my mother’s handwriting now”

on the image back. From top right:

Mrs. Clack, Douglass Clack, Edith Galt, Marjorie Hubbard, Ralph Galt,

Constance, Harold, Bertran (sp?) Hubbard, Gordon Clack, Table Boy

(in door window). “Table Boy is the Chinese servant that waited

on table... These [people] lived in Paotingfu.”

—EARR, Growing Up In China (GUiC),

Part I, March 1999

|

|

|

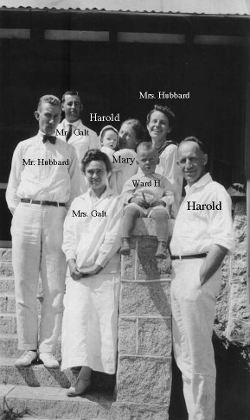

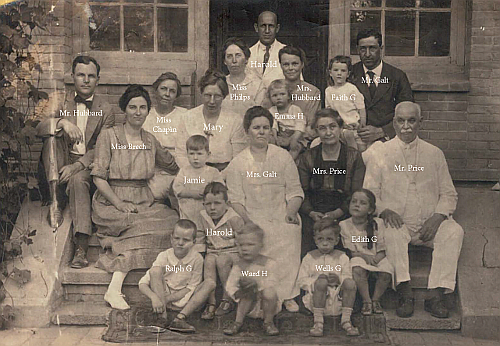

Robinsons and other American Board members in Paotingfu, circa 1922

“This is a little bit later than this birthday party, because

there’s little Jim, and the Hubbards now have moved into the

Hubbard’s house.... This is Grace Breck, I think. This is

Isabel Philps. She loved me a lot and I wasn’t yet born, but

when I had scarlet fever and was incarcerated in the third floor of

our house and my mother had to stay with me and nurse me—it must

have been terrible—and Harold wasn’t allowed to come

back from Tuchow (his boarding school) that Christmas vacation (and

he didn't like that), and Jim stayed downstairs with my father ...

So this is the kind of community I grew up in. And there were

always kids, but there were not as many—this is more kids

than I remember because by the time I came along the Hubbards were

living in that house.... And Mr. Hubbard, he was just wonderful ...

he was a minister. There is a book out called The Call

[by John Hersey, 1985] that’s really about him [and five others],

it’s a novel.”

—EARR, Growing Up In China (GUiC),

Part II, March 1999

|

|

|

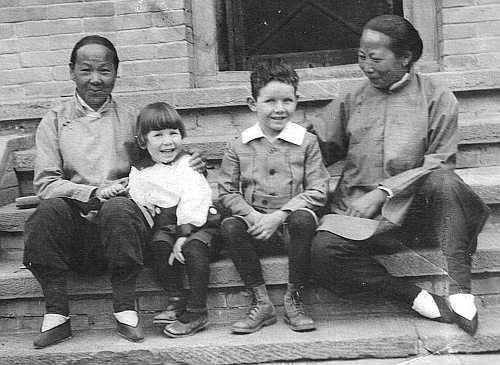

“Here are some bound feet. These are my two brothers’

Amahs. My Mother could go and teach english—she loved to

teach Walt Whitman, she loved Chinese poetry and she loved American

poetry.... She could write, better than my father could. She was the

literary person and it comes down [into Mary’s descendants]. This is

Jim’s Amah, and I think she was called, Wang Nai Nai

[Looking at the back of the picture, is the text:]

‘Amah and Sewing Woman with two Robinson boys’. This

is Wang Nai Nai and maybe this was our Sewing Woman

but it looks like she’s Harold’s Amah, too.... And I

think this may be the steps—not our front steps—but the

steps out of my father’s study door....

—EARR, Growing Up In China (GUiC),

Part II, March 1999

|

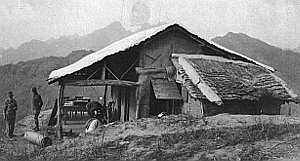

In Paotingfu The Robinsons lived in the building on the left and the building on the right housed the Galt and Hubbard families |

|

|

|

||

| Three different houses the Robinsons lived in during the 1920s and 1930s | ||||

|

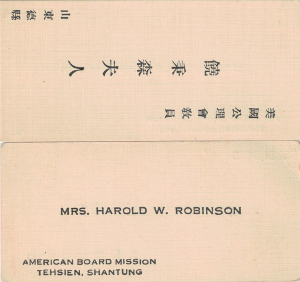

“This was my mother’s calling card after we moved to

[Tehchow in] Shantung Province and it probably says..., I don’t

know, it doesn’t say "r’ow tie tie". That probably is

"r’ow" – our chinese name was r’ow, the last

name was r’ow, and my father’s name was "r’ow

bing shun" (like Robinson). And my oldest brother Harold’s

name was "r’ow quay min" which has a meaning and I don’t

know what it means.... And Jim was "r’ow quay duh" –

"quay" would be repeated in each time. And I was not "r’ow

quay lepai", I was "r’ow quay j’un". They’re all

biblical in some way. And this probably, it says "r’ow

something something", this would be my mother’s name but

I don’t know what it was. But this is her calling card.”

—EARR, Growing Up In China (GUiC),

Part I, March 1999

|

|

|

|

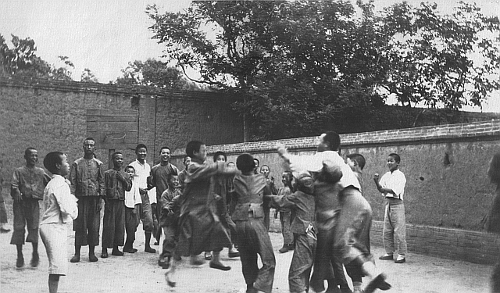

HWR’s writing on the back of this image: “A group of students on

the basket ball court at our Dartmouth School in Kao I. I played with

them after I took the picture where I was down there a few weeks ago.”

—EARR, Growing Up In China (GUiC),

Part I, March 1999

|

|

|

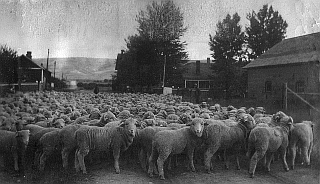

“This [is] our going-back-to-China passport picture and

everyone’s looking pretty serious.... It was a hard time

for [my mother]. We’d all been through a lot—although

I don’t remember it and I’m sure they

don’t—but, my mother had said after this seven-year

stint in China, she told Dad, your grandfather, that she would

not go back to China with him. He could go back but she

wouldn’t go—she hated it. So he said, ‘Well, I

love China but let me go and think about this. You’re my

wife and this is my family.’ And he went up and spent a

summer, or, I don’t know how long, three months or so, at

Guy and Bess’ ranch in Deer Lodge, Montana. He was a

shepherd. He took care of the sheep. My mother stayed with her

Mom in Long Beach in the little cottage that they built; it was

very cozy. But it must have been hard on my brothers. They must

have known: tension, tension, tension. And I don’t look

very happy there. When Grampa came back he said, What I really

want is to be with you and with my famiy and I’ll do

whatever you want. We’ll stay here. We’ll find

something to do here. By that time my mother had decided she

wouldn’t put him through that. And I don’t know

whether she cared anymore about China being that far away from

it, or she just thought she’d go back. So it must have been

a hard time.”

—EARR, Growing Up In China (GUiC),

Part II, March 1999

|

|

The Robinsons boarded the SS Calawaii in Los Angeles on

February, 14

1925 to return to China via Honolu. The following is Harold

Robinson’s recounting of this period culminating when he went

to Montana, from pages 79 to 81 of

Grandpa’s Story:

|

|

|

|

|

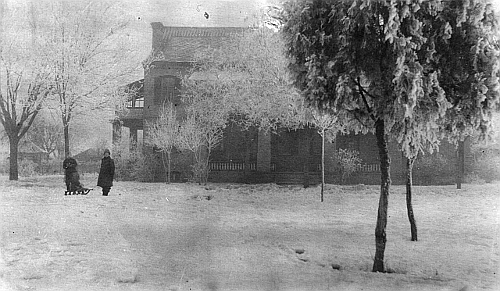

“So, we do go back to Paotingfu and here is our house and here

is the sleeping porch that I remember sleeping on...it was real cold

[in the winter] but we all had sleeping bags. And I remember that my

mother was hard—I mean she was so depressed and a difficult life

for her. I remember when I would go to bed on that sleeping porch I

would say my prayers and i would say—I made up a poem about,

I love the sleeping porch

It was comfortable. I could be cozy. And I knew that my mother

couldn’t be that way for me...[I was] five probably. Because

I do remember sitting someplace on my bed or her bed or the stairs

and realizing that there was nothing I could do to make her happy.

That’s really sad. And I think it was at that point that I

decided I had to take care of myself.”

My bed is my second mother |

|

|

“But you can see we had snow. There’s a sled. I

don’t know what Jim is holding. The snow would melt

pretty quickly. It didn’t last very long. But it was

cold.”

|

|

|

“I think I was probably a little bit younger here with my

doll babt carriage and that little doll in it. I remember we had

these walks, thick walks. I don’t know where that was but I must

have been about three, two or three there.”

|

|

|

“And here was our crew of servants. These were very

important people in my life. This is Tien Da Tsao, this is my

amah. And she is the one, she didn’t have bound feet. And I

loved her a lot she was just wonderful. Looks as if I have a

stomach ache [laughing]. And my brother Harold [more laughter],

having a grand time! And brother Jim looking up to see what thing

Harold is going to try next. This is our wonderful Cook, "Zang

Sha Fu" [man behind Jim]. He was just great. We loved him so

much. He was very funny. I don’t know how he did it but I

remember he, somebody came by that Zang Sha Fu didn’t like

and thought he was doing—some Chinese man—and he hung

him up by his heels...he was protecting us in some way and I was

very impressed. And I know that Zang Sha Fu was the cook and when

my mother taught him how to make American breakfast (you’ve

heard this story before), by mistake she burned the toast on the

Chinese stove and she scraped it and said, ‘We don’t

throw this out—but we’re not supposed to do

this.’ But Zang Sha Fu always burned the toast and scraped

it. And this was the Gardner [behind Harold]—he was not

particularly important, he did a lot of things outside. And this

was the Table Boy [behind Elizabeth]. His name was "Bwa Lin", Bwa

Lin was our Table Boy. Zang Sha Fu was the Cook. "Shri Fu" means

Head Person. And Bwa Lin was his name. He didn’t have the

charisma that Zang Sha Fu did. He didn’t love us as much as

Zang Sha Fu did...

—EARR, Growing Up In China (GUiC),

Part II, March 1999

|

|

|

“This, I don’t know who it is. It’s probably Harold. This is

how—although I went one summer, I think, with them, to

Gwantzeling and it might have been me—this is how the

little ones went up the mountain, in a chair with bearers

carrying us.”

|

|

|

“This is in Paotingful and here’s Jim and Emma Rose and

they’re wearing Chinese padded garments, they’re very warm

coats. This is, I think...might have been Faith Galt—maybe

the Galts lived with the Hubbards for a while too. So I think

that’s Faith Galt or one of the Galts and this is me [between

Emma Rose and Faith]...Cold winter.”

|

|

|

“And this, by contrast in Peitaiho, is where we went for

the summers and it’s beautiful, wonderful Pacific ocean,

down at the beach where we spent lots and lots of time. I

think I was just skinny-dipping. Loved it, it was warm and we

had total freedom there. We as foreigners had the place all to

ourselves. Chinese didn’t live there.”

|

|

|

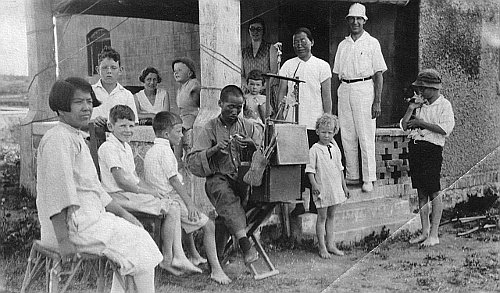

“This house was built there, and I think my folks paid for

it. Across the way was the Ballou’s house. This is Mrs. [Thelma]

Ballou [immediately to right of pillar on the porch]...The fathers

would be there only part of the summer; the mothers would be there

with their kids. This is my father [with white hat on porch], this

is my mother [second person to left of pillar], Harold looking

very sad [to the right of Mary]—Mrs. Hubbard Ballou who just

died last year. I think this is their amah [to the left of Harold],

Bobbie Ballou, Jim [in front of Harold], Larry Ballou, little me,

and this is Cristy Ballou [right of pillar]. That’s me

looking really sad. I might have...well, I don’t think that—I

think I was younger when I was punished, probably about this age,

I was punished because our amah would go with—my amah,

Tien Da Tsao, would go with me. And she was told to bring me

back for a lunch. We’d always have a big lunch in the middle of

the day and then take a nap. I didn’t want to come back. So I

bit her in the shoulder, enough to make it bleed. And she would

have clothes on. My father had just arrived from Paotingfu and

the family had been there for some time without him. He had

brought lollipops for everybody. And my punishment was, I had to

give her my lollipops. That was a punishment. And I remember

that!...I think that’s when I was about five. This looks like

when I was about two or three. But really not very happy. Maybe

I had been playing and they called me to come. [Harold Robinson

wrote on the back of the photograph:]

This was taken at Peitaiho last summer. Mrs. Ballou is standing

on the porch as is her amah. Bobby is at the left and Christy is

at the right of the porch pillar. Larry is near James and Hubbard

is holding his pup in front of the porch. Mr. [Hubbard] Ballou

took the picture. The center of attraction is the man who made all

sorts of figures out of dough and coloring matter. Some bunch when

the two families got together.

“He was a travelling guy, he walked around and carried this

on his back. And he made these wonderful figures out of flour and

water and painted them. He was very artistic. He did it for

the Chinese kids and then of course he would make more money if

he came around to the westerners. This house was where

we—this was at Lighthouse Point. And later on, because

there was just the Ballou family house over here and our

family house in Lighthouse Point and the beach was practically

empty—it was just our two families—now, the

Communists have taken it, of course—it was all foreign.

And now it’s a big place for R and R for Chinese officials,

Communist officials. And it’s changed a lot. People who have

been back don’t recognize it, saying this house is gone.

|

|

|

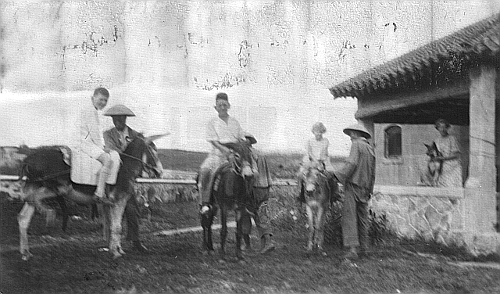

“This is how we got to and from the train by donkey. This was

probably—we had a dog named Casseopia. That’s probably

Casseopia.

—EARR, Growing Up In China (GUiC),

Part II, March 1999

|

NCAS back of girl’s dormitory |

|

Harold and Mary Robinson in Tungchow, 1938

|