∧

FIRST MEMORIES

The photograph is slightly yellowed, but still quite clear. That

white haired woman wearing an apron, is my paternal grandmother,

and she smiles as she cradles the new baby, swallowed up in a

long white dress of that era. You can’t see the

baby’s face very well, but because my family has told me, I

know who it is. She was given her mother’s middle name of

Elizabeth, and her maternal grandmother’s first name, Adda,

for her middle-name, and her father’s last name of

Robinson. So her initials are EAR.—She is I.

The photograph is slightly yellowed, but still quite clear. That

white haired woman wearing an apron, is my paternal grandmother,

and she smiles as she cradles the new baby, swallowed up in a

long white dress of that era. You can’t see the

baby’s face very well, but because my family has told me, I

know who it is. She was given her mother’s middle name of

Elizabeth, and her maternal grandmother’s first name, Adda,

for her middle-name, and her father’s last name of

Robinson. So her initials are EAR.—She is I.

Although probably conceived in China, I first entered the world in Barre, Vt., my father’s home state, on my parents’ first furlough. My mother was 40, not young. But I imagine that for her this birth was far easier than my China-born brothers’ when a rickshaw was the conveyance called as time came to go across the city to the hospital. This time it must have felt good to be on American soil, and with flesh and blood real family to help take care of both new mother and child.

Although I don't remember anything about my first months in

America, I have been told that the family moved from New England,

my father's home, to Long Beach, California where my mother's

parents had built a little cottage behind their home, to house

us. Once settled in here, my mother began to dread returning to

China, and told my father she had decided to stay in the U.S. He

was able to understand her feelings and needing some time to

reconsider his choice of career, as a missionary, suggested that

he go to Montana and spend several months on my mother's

brother's sheep ranch. Alone in the mountains, under the Big Sky

with only the sheep as companions, he could meditate and think.

The family mythology has it that in my mother's own time by

herself, to meditate and think, she came to the conclusion that

actually life in China had some good points, and she really

didn't want to be the cause of her husband's giving up a career

he had come to love. So when my father came down from the

mountains ready to readjust his life, he found his wife ready to

pack up the little family and return to China! Eventually, she

too came to love that country. It was in Long Beach that the

first family-of-five passport photograph was taken, for our

return to China. I was then a year and a half.

my father's home, to Long Beach, California where my mother's

parents had built a little cottage behind their home, to house

us. Once settled in here, my mother began to dread returning to

China, and told my father she had decided to stay in the U.S. He

was able to understand her feelings and needing some time to

reconsider his choice of career, as a missionary, suggested that

he go to Montana and spend several months on my mother's

brother's sheep ranch. Alone in the mountains, under the Big Sky

with only the sheep as companions, he could meditate and think.

The family mythology has it that in my mother's own time by

herself, to meditate and think, she came to the conclusion that

actually life in China had some good points, and she really

didn't want to be the cause of her husband's giving up a career

he had come to love. So when my father came down from the

mountains ready to readjust his life, he found his wife ready to

pack up the little family and return to China! Eventually, she

too came to love that country. It was in Long Beach that the

first family-of-five passport photograph was taken, for our

return to China. I was then a year and a half.

My first real visual China memories center on the family’s sleeping arrangements. Our grey brick two-story house had a sleeping porch, and it was here that all five of us slept. In the winter, flannel lined sleeping bags kept us warm and cozy.

In the spring and early summer the sleeping bags were traded in for mosquito nets which were slung from four pegs in the ceiling, hanging down to outline the bed and keep the buzzing mosquitoes outside rather than inside attacking whatever skin they could find. For me the sleeping porch provided a sense of deep comfort and safety. I remember at some point, making up a little poem that began, “My bed is my second mother”. Here all the family shared space and sleep—my parents, two older bothers and me. Although our bedtimes varied, somehow to wake in the night and know I was surrounded by everyone I loved and who loved me, provided a sense of being close to God. I can remember thinking as I listened to the soft and deep snuffles of my parents snoring, that probably God sounded like that.

I, like my brothers, had several names. The Chinese name I was given shared the first word with that of both brothers: “Kui”, meaning great, or important. The second part “Jen” might be translated as “precious” or “pearl”. A special vegetable name given my brothers by our cook, never was gifted me; I was simply known to him as “Kui Jen” Within the family my pet name was “Little Bit” which I carried until the Hunter family moved into our compound. Jean, just my age, became my inseparable playmate. When our brothers wanted us for some reason or other, they combined our two names into a much used Chinese phrase: “Lepai gee?”, meaning “what day of the week is it?” (in those days most Chinese needed to know what day it was more than what hour it was). When Jean and her family left our compound, I simply acquired the name of “Lepai”. It was so deeply imprinted, that when I went off to college in the U.S., I had to decide whether I would say my name was Elizabeth (which I hadn’t been called all through boarding high school), or “Lepai”, by which I had been known ever since Jean Hunter came into my life around age 6. I choose to be “Lepai” and to this day I am still known by my oldest friends and family by this unusual Chinese name, which by the way is also the name of a famous Tang Dynasty 8th Century poet.

Missionaries abroad kept in touch with their U.S. families by writing long Christmas letters, that covered changes in height and weight as well as the major illnesses and children’p clever sayings of the previous year. Of course there were no computers so these were typewritten on thin sheets of paper and mimeographed copies sent to various family branches back home. My parents Christmas letter, “The Chinese Chimes”, was written as if our family were some sort of well ordered corporate venture. Father became “Editor (Pretend),” mother was “Busy Manager,” Harold was “Cub-Reporter,” James, “Sport Editor,” and I, the “Treasurer”—metamorphosed in the Chimes into the “Treasure,” by virtue of my being the only girl, last child.

Each of us children had an amah, to take care of us while our mother was busy teaching in the mission school, and running the household. Amahs lived in their own homes in the Chinese city, but came to our compound during the daytime. Our amahs played with us, told us endless stories, put us down and got us up from naps, made sure our clothes were clean and did everything that was fun and time-consuming, that mothers in the States at that time in history enjoyed doing with and for their kids...

Harold’s Wang Nai Nai, became James’ amah after Harold became old enough to go about his business as “a big boy”. I imagine that James before he inherited her, had his own loving amah, but I never knew about her. From the many family photographs taken by our father, Wang Nai Nai’s lovingly crinkled, weather-beaten face smiles forth. She must have been close to 60, and she had the tiny triangular shaped bound feet required by the Manchu dynasty into which she had been born. Encased in self-made black cloth shoes, in my minds eye I can still see her tottering about in a delicate running step. No matter how tired or upset she might be, Wang Nai Nai always seemed to be ready to comfort and console her little charge. And although she was James’ amah, I loved her as much as he did.

My own amah was younger than Wang Nai Nai. Probably around 35 or 40, Tien Da Tsao, had the natural large feet of women born after the Manchus no longer held China in thrall. Her face was smooth without wrinkles, and the skin had a rosy youthful glow. She wore tiny gold earrings, but no wedding ring, and I never knew whether she had a family of her own. Amahs never talked about their own lives, dedicating themselves totally to their “day work”. She was my beloved constant companion, doling out soothing comfort when my feelings or body were bruised. She told me wonderful Chinese folk tales of “Chu Ba Cheh” (the clever pig) and his friend, “Tsun Hoer” (the monkey king), and sang me silly Chinese opera songs when I was ready to listen to their strange wails and high pitched tunes. She dabbed my “ouchies” with mercurochrome, and cooled my forehead if I had a fever and mother could not be with me at home. When not with me, she could be found in the sewing room where she made the sewing machine whirr with her skillful peddling. Here she created and mended clothes, darned sox, and hand stitched beautifully designed quilts to cover and warm our beds at night—when she had left for the Chinese city and her (to me unknown) own home.

After Jean Hunter’s family left the Paotingfu compound, and I no longer had a little girl to play with, Tien Da Tsao became my playmate, teaching me new games and showing me how to embroider and make clothes for my dollies. I loved her as if she were my own mother, and when the mission board transferred us from Paotingfu to Techow in Shantung province, I begged that Tien Da Tsao move with our family to this new compound, where there were no other families with children. Since it was rare for amahs to move away from their own home towns, if their employers were transferred, I felt overjoyed when she agree to come with us—at least, I was made to understand—on a trial basis. As I remember, Tien Da Tsao stayed with our family in Techow until it came time for us to come back to the U.S. on furlough when I was 8 years old. For perhaps a year then, Tien Da Tsao and a newly purchased little pekingese dog I named Pickles, were my only playmates. It must have been a strange and lonely year for my beloved amah, but she never complained, and seemed to make friends with the new crew of servants we inherited. I suppose we gave her extra severance money and I never knew what she did after our family sailed off to America.

Our furlough lasted a year and a half, and when we returned to the Techow compound, there were two other families with children. I was ten by then, and remember as if it were only yesterday, my terrible disappointment when, on our usual summer vacation spent in Peitaiho, I unexpectedly ran into Tien Da Tsao. She was at the beach taking care of a little blond haired boy, and when I ran to greet her with joyful surprise and pleasure, she seemed to not recognize who I was. In my gawky new 10 year old body and face, I still felt the same, but to her I was just another foreign child. It was a hard learning for me to realize that sometimes one’s beloved can change into just another person out of the past. I suppose she may have felt somewhat like that when we sailed off and left her.

During one of the local Paotingfu war lord’s violent battles which brought bullets and roving soldiers too close for comfort, the missionaries were moved to a safer city outside Peking. For several months, our family was housed with another evacuated missionary family in Tungchow. I must have been about 3 and don’t remember this stay, but because of hearing several events repeated many times, feel as if I actually can see the little beastie I must have been.

Both evacuated families ate together in the dining room, and one supper time, I was interrupting an otherwise normal meal by behaving outrageously in my highchair—probably banging my spoon and screaming for attention. Apparently I refused to quiet down and caused such a ruckus that my parents removed me and my highchair to a back hall away from the dining room. Not to be banished so summarily, I fought back by banging my spook on the highchair tray, yelling over and over at the top of my lungs this phrase, “Please help little Bimbo!” “Please help little Bimbo!”

Who knows where the “little Bimbo” phrase came from, but it might be connected in some way with the second event that I “remember” by hearsay. This occurred not in the dining room with others present, but in an upstairs bedroom, where I was sick with tonsillitis. The missionary doctor had been called from his duties at the hospital, and came, carrying the traditional black doctors bag. After checking my throat he told me to “Open wide” and approached to do the usual mercurochrome covered cotton swab treatment. However, from the hearsay reports, my screams could be heard far from the upstairs bedroom! Yelling protestations and thrashing wildly about I refused to open my mouth. Finally, with my mother assisting, the curative medicine could be applied and another minor sore throat could be healed. Although I don’t actually remember who it was that had caused me to be so terrified of the so-often used red mercurochrome swab. But someone, probably one of my brothers, must have had teased me by telling me red mercurochrome was really red monkey’s blood! And it’s quite possible that “Little Bimbo” was the name of a monkey in one of my story books. Now who would ever have thought to tease a little sister with such nonsense!

With the ending of the war lord’s fierce fighting in Paotingfu, we returned from our short term evacuation to our own compound with its two storied grey brick house and second floor sleeping porch. Here we lived many peaceful years while mother homeschooled all three of us siblings. I still can see the little upstairs alcove where her desk and ours stood close together in the morning sunlight.

The Calvert System was the method of teaching all three of us, until boarding school provided seventh grade intellectual material for our minds, and socialization and sports for our physical selves, with American and other foreign children who lived in various interior parts of China. My brothers had long since gone off to boarding school by the time I can remember sitting at my little desk beside my mother’s big one. The Calvert System seems to me to have been way ahead of the Dick and Jane method with which my own four children learned to read.

The Greek myths were my first reading books, selected by the Calvert people as appropriate stories for beginning readers! Not exactly Dick and Jane and Spot, these very human-like tales of gods and goddesses opened my eyes to how families interact, not always in perfect harmony, but somehow managing to keep the four seasons in orderly rotation, darkness and light in balance, war and peace alternating, and the battle of the sexes alive! They provided a simple faith and explanation of how things tend to work out even when it seems that all may be lost. As a little girl, reading stories about the tumultuous uproars occurring within families of these powerful gods, helped me accept the scary confusion of relational upsets which occurred in my own flesh and blood family of five. They provided a sort of reassurance and comforting humor that things would work out. As a consequence, I have always been grateful to, and fond of, the mythic intergenerational families dwelling on Mt. Olympus!

Along with an appreciation of the power of myth learned at the little desk by my mother’s knee, I am grateful that she was able to devote her patience to my particular unique needs. Since there were only the two of us, in that upstairs sunlit alcove, my abilities never were compared with another child’s. So my mother/teacher could supply reassurance and support when my intellectual capacities required her acceptance and encouragement. I was a slow reader, I formed my letters backwards, and mixed up the order of numbers in arithmetic, my attempts to print and later to write cursive were awkward and messy. All these specific difficulties she treated as not at all unusual—as perfectly fine. So that I never had any reason to think of myself as different. My mother gave me a sense of being able to accomplish tasks even if they were difficult.

In high school I passed geometry only because the teacher thought my long winded proofs to theorems were hilariously creative. In college I was reproved by the dean for my poor writing, and impossible spelling. Yet, somehow my brain produced interesting thoughts; I loved to learn and worked hard, taking longer than most to complete an assignment; I loved to read and was excited by new ideas. I went through college on scholarship. I was never diagnosed as certifiably mentally incapacitated in any way.

Innocence they say is bliss. And so I have lived. Until two weeks ago, when I attended a psychological workshop titled “Disruptive Behavior Spectrum Disorder”. The focus was on how children learn in different ways, and how these differences create frustration for themselves and their teachers. Their behaviors in class reflect these frustrations often causing terrible disruptions in their intellectual and character development. One of the presented learning differences focused on hand/eye coordination which originates in a specific area of the brain. About fifty years ago this learning difference was given a name: DYSLEXIA. And children having this difficulty are now easily spotted in the early grades and often become “special education” kids. Singled out as “different”, of course stigmatizes them for life.

So how is it that in a psychological workshop taken because I needed “Continuing Education Units”, I lost my innocence? Well, we were given several exercises to experience the frustration and anger these Special Ed students feel when given certain tasks. One of the tasks was to duplicate a simple line drawing, which you could see only in a mirror held to reflect the drawing. My partner went first and had no trouble at all in this task. But when I tried, I nearly went crazy! I could NOT make my hand move the pencil to duplicate the simple form. No matter how I tried, the pencil simply would not move off its perch. What ever direction I tried the movement rebelled. All I could do was make chicken scratches over and over! I experienced real rage and felt like crying. It was an experience I will never forget. Especially because I realized how fortunate I have been living with dyslexia all my life and never knowing it.

I can come up with no moral to this story. It is simply a reminder that there remains much more for which to be grateful than I can ever realize, even at the age of 83! So perhaps belatedly I say “Thank You” to my parents. And then I will end with a five fold “AMEN!”.

∧

MY FIRST TRIP TO CHINA

WHEN WILL IT EVER END...

WHEN WILL IT EVERRRRR END?

PART I

PART II

To paraphrase Wordsworth, “The world is too much with us; late and soon, getting and spending (in wars) we lay waste our powers”. Again today, in August 2013, we seem to be facing the very real possibility of going to war.... I don’t remember the very first WAR that dovetailed with my personal life...although I have been told it occurred before I was born in 1923. It was then that my missionary family went on its first furlough, after seven years in China.

The first half of that furlough year was spent with my mother’s West coast Long Beach parents, the second half with my dad’s Vermont family. At that time, this little Robinson family consisted of dad, his very pregnant wife, and two little China-born brothers. In Long Beach dad had bought a lumberingly safe used Buick car to drive across the country, and it must have been quite a trip with two actively competitive little kids in the back seat, and their uncomfortably very pregnant mother up front. Mother’s due date came sometime after they landed in Vermont, which accounts for the fact that I was born across the country—in Barre, Vermont where we spent the next six months.

Following those New England months, my assumption is that we drove back across the country to Long Beach so that mother’s family could meet me—the latest family addition—before we were due to board ship and return to China. However that return was delayed due to some sort of warlording going on in Hopei province, where my parents’ first assigned mission station was located in the capital walled city of Paotingfu.

It wasn’t clear just how long our furlough would be protracted, and I imagine that once safely back in the bosom of her own family, my shy, travel-weary mother heaved a great sign of relief. The story has it that, feeling secure in familiar American surroundings again, she announced to her husband that, although for those past seven years she had put on the best face she could, actually, she had hated their years in China. She was bone tired. Now that at last she could relax, face and express aloud her real feelings, she had decided she would not return to China to raise their growing family. If he wanted to live the life of a missionary to China, he would have to do it alone, or at least without her.

Although disappointed and saddened, dad—who had loved discovering China and its people—heard his wife’s heavyheartedness and realized that he could find satisfying work other places in the States. The important thing was to do something in which his wife also could find happiness. This being so, he assured her that they didn’t HAVE TO LIVE in China. Given this unexpected extended furlough time, actually gave them a chance to seek out some other place to live and raise their family together. Mother, now could relax into her new motherhood, knowing that her needs had been heard.

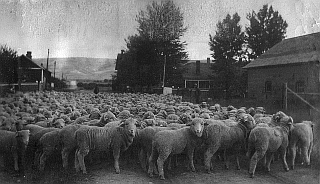

Not too much after this, Uncle Guy, mother’s sheep rancher

brother in Montana, wrote a letter saying that his regular summer

mountain sheepherder wasn’t available, and he wondered if

possibly dad might be able to fill in until another man could be

located. Providence had indeed intervened! What an opportunity!

Dad gladly accepted the offer to wander Montana’s

undeveloped wild mountains, as shepherd to his

brother-in-law’s flock of special Rambouillet sheep in

their annual summer pasturing. As for my mother:—quite likely

she felt greatly relieved. She, the mother of three little ones,

could catch her breath, surrounded by her own people in her own

country, knowing that her husband had heard her needs, and she

should not feel guilty since here was almost a 23rd Psalm answer

to their prayers.

undeveloped wild mountains, as shepherd to his

brother-in-law’s flock of special Rambouillet sheep in

their annual summer pasturing. As for my mother:—quite likely

she felt greatly relieved. She, the mother of three little ones,

could catch her breath, surrounded by her own people in her own

country, knowing that her husband had heard her needs, and she

should not feel guilty since here was almost a 23rd Psalm answer

to their prayers.

When dad returned from his Montana summer mountain adventures, he brought with him a new vision of life’s possibilities. As he had shepherded the sheep—wandering the wild mountains during the day, and at night joining them sleeping under the star-lit open skies—he had plenty of time to contemplate the future. So when he returned to mother in Long Beach, refreshed after their separation, he told her that he didn’t HAVE TO go back to China. They had time to look around, here in the U.S, for an appropriate pastorate where they could raise their little family together, and she could enjoy being an American housewife and mother. For her part—having just experienced two months running a household while caring for three small children without willing servants and Chinese amahs to help—she now was able to view her life in China with different eyes. By comparison, missionary life looked like heaven. And she gladly set to trunk and baggage packing, once the warlording ceased in Paotingfu, and the mission board could book passage on the next President Line ship.

From hearsay, rather than from personal memory, my first taste of China was undoubtedly accompanied by certain characteristically offensive smells that seemed to be a part of the mid-1910s China where I spent my early life...We foreigners lived in “safe”walled-off compounds, but for the ordinary Chinese people, staying alive was not easy. Disease was always waiting around the corner; all life was cheap, and under the circumstances “public health” unknown. Villages and cities were crowded, and for most people dumping garbage in the streets, was just a part of daily living. One of the familiar street calls of village life was that of the “night soil” man as he wandered through dark streets collecting whatever he found dumped during the previous day. Outside every tiny hamlet a small grove of trees always clustered around the local graveyard which, in spite of the fact that it took up precious crop planting space was treated as sacred ground by the villagers, since “the dead” were to be honored lest their ghosts return bringing unpredictable sorts of bad luck.

WHEN WILL IT EVER END... WHEN WILL IT EVERRRRR END?PART I

PART II

Since I was only about 18 months old, I don’t remember

anything about my first trip to China. From hearsay I know that

our family of five (instead of the original four who had left China

many months earlier) landed at T’ianjing in the late

spring of 1925. From a passport photo of that era, a little

curly haired girl squirming in her mother’s lap looks

worried, while at either side of the parental center stand two

uncomfortably well groomed boys, aged about 5 and 8. The

Robinson family was re-entering missionary life, and would now

travel by train across the dry flat plains of North China to

Paotingfu, the capital city of Hopei province. One of the major

Since I was only about 18 months old, I don’t remember

anything about my first trip to China. From hearsay I know that

our family of five (instead of the original four who had left China

many months earlier) landed at T’ianjing in the late

spring of 1925. From a passport photo of that era, a little

curly haired girl squirming in her mother’s lap looks

worried, while at either side of the parental center stand two

uncomfortably well groomed boys, aged about 5 and 8. The

Robinson family was re-entering missionary life, and would now

travel by train across the dry flat plains of North China to

Paotingfu, the capital city of Hopei province. One of the major

war lords of this era, Jiang T’so Ling, originated from

Paotingfu, although we never encountered him or any of his

entourage, since we lived safely in our walled compound which was

outside of he city wall. However, our family life in Paotingfu

was several times interrupted by various war lords fighting in

areas close to this capital city.

war lords of this era, Jiang T’so Ling, originated from

Paotingfu, although we never encountered him or any of his

entourage, since we lived safely in our walled compound which was

outside of he city wall. However, our family life in Paotingfu

was several times interrupted by various war lords fighting in

areas close to this capital city.

Back in Boston (previous to our returning to China after this first furlough) the mission board had decided that the Robinson family be permanently located in a walled and gated compound situated outside the walled city of Paotingfu. Besides our house, there were in the compound two other missionary houses, living quarters for Chinese staff people, a tennis court, several goat pens to house our close-at-hand source of fresh milk, and a large vegetable garden in which vegetables were grown and could subsequently be safely eaten raw. Sharing space in this large well-designed compound with the western style houses, were two schools—one for Chinese boys the other for Chinese girls. Besides these two schools for formal education, there was a “gung chiang” (sort of a workshop) for Chinese girls and women. My mother taught English in the schools, and helped to run the women’s workshop, in which were created beautiful needle work items of all sorts from the sale of which the women earned money that otherwise they would never have had. Besides this mission work, mother homeschooled us three kids from 1st through 6th grade, using “the Calvert System”, founded for people teaching their kids at home (and I believe still extant today, for this same purpose).

My Dad had an office on the first floor of our house, but most of the time he was away in the countryside. His means of transport was his trusty bicycle, which took him way beyond the compound wall far into the open country areas of Hopei province. Both he and my mother (like all China missionaries of that era) had spent a full year at the Peking Language School, learning Chinese before being assigned a mission station where they would finally find their laboriously acquired language skills useful in their work. Dad’s work out there in the mostly flat open country surrounding Paotingfu, involved riding his bike to visit, (or preach) in already established tiny house churches, sometimes also helping establish such churches. Besides this work, he often joined others doing relief work following floods, fires, or devastation caused by local war lord factions, fighting within Hopei.

During these years of the 20th century in North China, warlords were constantly fighting each other—one dominating certain areas for several years, until replaced by another. Some names I can recall: Jiang Hsieh Liang, Yuan Hsieh Kai, Jiang T’so Ling, and of course Jiang Kai Shik, later to be President Jiang Kai Shik—who, with his Wellesley College-educated wife, Mei Ling Sung, eventually left mainland China, for the island of Formosa, also called Tai Wan. My family’s home town, Paotingfu—as the capital city of Hopei province—seems to have been one of the major centers of back and forth fighting, causing the Robinson family several times to leave our “safe” little compound. Once to Tungchow, a city 14 miles outside of Peking, once to Guan T’so Ling, an isolated mountainous area in Shantung province, and once to stay with missionary friends in Korea. MY early childhood was, thus, constantly having to deal with wars in which we were not involved, except as we needed to flee our home base to escape bullets flying over our otherwise safe mission compound.

And so it seems, fighting wars continues as a deeply ingraianed addiction, co-existing within so-called Civilization. As human beings have evolved into complex societies, so have the complex behaviors we create to express our unique social structures and beliefs. We have international cooperative organizations, shared educational undertakings, inter-governmental humanitarian projects—all aiming to protect and foster peaceful cooperation among desperate groups of people. And yet still buried underneath all these consciously constructed, socially responsible structures and behaviors, primitive muffled drumbeats can be sensed, if one bends over and assumes a prone rather than an upright position, and puts an ear against the earth, on which we are, after all, rooted.

Since I started to write this piece in early August, two months have passed, and so far as I am aware we are still “at peace”. Why is it then that I continue to feel restlessly anxious and on edge at days end, waiting to turn on the evening news, to see how the world is doing at this moment in history? Maybe the expression “at peace” is some sort of cover for not being formally “at war”? Meaning actually that right at this very moment we are not involved in a declared war going on somewhere “out there”?

Maybe “the times” that we now are living through, actually represent isolated stages between the times that we are not actively involved in “declared” war anywhere. Like the era of my early childhood, when formally China was peaceful, although warlords were actively engaged in skirmishes between themselves all over the country. So we can continue to sing that familiar chorus “When will it ever end, when WILL it EVER END?”

∧

MY FIRST REMEMBERED HOME

MY FIRST MEMORIES OF HOME TAKE ME TO Paotingfu, China, where my

parents were missionaries. We lived in a big grey-brick

three-storied house set on a smallish plot of land. Our yard

stood in a large walled compound shared by two other big grey

brick three-storied houses where other families and single women

missionaries lived. Our house had a screened sleeping porch

across one side of the second story where our family of five

slept in freezing cold or hot summer. In the winter heavy

sleeping bags felt like warm cocoons to snuggle all the way down

into, except for my head that loved feeling the sharp cold

contrasting with the warmth of my body.

MY FIRST MEMORIES OF HOME TAKE ME TO Paotingfu, China, where my

parents were missionaries. We lived in a big grey-brick

three-storied house set on a smallish plot of land. Our yard

stood in a large walled compound shared by two other big grey

brick three-storied houses where other families and single women

missionaries lived. Our house had a screened sleeping porch

across one side of the second story where our family of five

slept in freezing cold or hot summer. In the winter heavy

sleeping bags felt like warm cocoons to snuggle all the way down

into, except for my head that loved feeling the sharp cold

contrasting with the warmth of my body.

In the spring and early summer the sleeping bags were traded in for mosquito nets which were slung from four pegs in the ceiling, hanging down to outline the bed and keep the buzzing mosquitoes outside rather inside attacking whatever skin they could find. For me the sleeping porch provided a sense of deep comfort and safety. Here all the family shared space and sleep—my parents, two older brothers and me. And although our bedtimes varied, somehow to wake in the night and know I was surrounded by everyone I loved and who loved me, gave me a sense of being close to God I can remember thinking as I listened to the softer and deeper snuffles of my parents snoring, that probably God sounded like that.

Both my parents worked outside the house. My mother taught English in the boys high school located adjacent to and outside of the compound wall, and my father was a math teacher in the same school, as well as being a bicycle riding circuit-rider minister visiting small churches in the country outside the walls of Paotingfu city. On these country visits he might be gone several days so that his return home was always a special time for the family. Especially for me, the littlest one and only girl, for he would allow me to crawl up and sit on his lap while he worked at his desk in “THE study”.

Although my mother was primarily “mother” to us kids, she was kept busy with household and teaching duties and, as was the custom for foreigners living in China at that time, we all three had Chinese amahs who took care of us and whom we deeply loved, probably much as Southern white children were cared for and loved by Negro mammies. Our amahs played with us, told us endless Chinese stories, put us down and got us up from naps, made sure our clothes were clean and in general did everything that was fun and time-consuming that mothers in the States at that time in history enjoyed doing with and for their kids. Our mother did other things. Besides home schooling her three children from what was called “the Calvert System”, she prepared English lessons and taught classes for her Chinese students, conferred with the cook and doled out money for him to shop for and cook our daily meals, planned tasks for the sewing woman (who some years served also as the amah), supervised laundry and food supplies kept in the store-room which the houseboy had access to as needed, and in general served as trouble shooter when problems came up while my father was away riding his bicycle around the countryside. To this way of life she had had a chance to adjust during the six years between the birth of my oldest brother and me, and I imagine that by the time I came along, she thought of herself more as efficient household manager and teacher than as soft and gentle mother. My memory of those childhood years is of being with my beloved amah rather than with my mother. This psychic fact is reflected in a mantra I remember making up as I lay all alone on the sleeping porch in my bed, after my brothers were old enough to both go away to boarding school. I must have soothed and comforted myself by repeating the rhythmic sounds of these six rhythmic words: “My bed is my second mother.” As I think about it now, I realize that if I felt that a nonhuman piece of furniture was a stand-in mother, I must have missed and longed for my real flesh and blood mother, and that this feeling must in some measure have been matched by her sense of being isolated from her children. Seeing this from such a great distance I feel sad.

∧

MY FIRST SCHOOL

My first memories of school involved sitting in a small chair close to my mother who sat at her big desk at the end of our upstairs hallway. Our school room was a wide alcove where my mother’s desk stood solemnly against the double window. It was here that she sat to prepare English lessons for her Chinese students, did household accounts, wrote detailed letters home to the States, and followed the Calvert Home Schooling system for my two older brothers and myself. Since my brothers were three and six years older than me their schooling was three and six years ahead of mine and I don’t remember sharing lesson times with them. Probably by the time I was six and in the first grade, they were going across the mission compound to the Hubbard’s house, to be taught by Mrs. Hubbard, along with Wells and Ward, who were about their same ages.

Except for Greek myths I don’t remember much about what I learned at my mother’s knee. The Calvert system, in those days, utilized stories from Greek mythology to teach reading skills. As a consequence, tales of Zeus’ various amorous and warlike adventures along with the all too human gods and goddesses of the Greek Pantheon atop Mount Olympus, peopled my imagination all my life, in place of tales of Dick, Jane and Spot that peopled my children’s early reading.

Since in my early school years I was my mother’s only pupil and therefore had the benefit of her focused attention, there was no one to compare me with and my mother simply assumed my way of learning was “slowly”, rather than that there was something wrong with her youngest child, only daughter. My spelling was often creative, and sometimes I wrote my numbers backwards. But mother didn’t scold, just gently corrected me. Nothing was ever brought to my attention about being “different” from other kids. Because in my little world there weren’t any other kids, in my class.

When I was eight, it came time for my family to return to the

States on furlough, and I was entered in the local public

elementary school, as a third grader. One major task was to learn

the “times tables”, and as I recall, this was no

problem for me. We chanted them off rhythmically by rote, and I

always loved to sing...(even if this wasn’t really

singing). “Miss Hollan,” my Long Beach, California

teacher, apparently considered me one of her

“helpers,” since she sat me next to one of my slower

classmates, David Wise. David was a nice kid, but needed help in

both arithmetic and reading, and apparently I served that

function O.K., since I remember little from that class except

these two names:—my teacher Miss Hollan, and my seat mate

David Wise.

When I was eight, it came time for my family to return to the

States on furlough, and I was entered in the local public

elementary school, as a third grader. One major task was to learn

the “times tables”, and as I recall, this was no

problem for me. We chanted them off rhythmically by rote, and I

always loved to sing...(even if this wasn’t really

singing). “Miss Hollan,” my Long Beach, California

teacher, apparently considered me one of her

“helpers,” since she sat me next to one of my slower

classmates, David Wise. David was a nice kid, but needed help in

both arithmetic and reading, and apparently I served that

function O.K., since I remember little from that class except

these two names:—my teacher Miss Hollan, and my seat mate

David Wise.

In this big American public school, my major “difficulty”, if you could call it that, was in recess out on the playground . So when the song said “Now put your right foot in....and take your left foot out”, I got confused.... Until one day when an ugly large wart sprouted up on the palm of my hand...I learned by experience that it was on my right hand, and always, thereafter, I could sneak a feel and know which was to be “put in” or “taken out” when that part of the song came along. Although the wart has been gone more than 80 years, in my “mind’s eye” I can still feel where it is...or rather—was. And I am grateful for the life-long assistance it unwittingly provided.

Thinking about these early years and their various contributions to my life, it occurs to me that while often life goes along seemingly smoothly or even with unexpected interruptions, a person doesn’t know when or what will actually be of memorable importance in the long run. Only in relatively recent years have I learned the word “dyslexia”. And although I have a fairly mild form of this, other more serious dyslexics, today will often be separated off from “normal” learners. I was among the lucky ones because when I began school, my first teacher (my mother) accepted my form learning merely as “A WAY OF LEARNING”, different from but not necessarily lesser than, any other. Not pejorative, just my way. Thus, I have been able to enjoy learning, and go through many different schools on a variety of scholarships. My sort of “differentness” wasn’t classed as stupid but as creative! And in the eyes of the world, what a world of difference there is between those two words. Shakespeare asked “What’s in a word?” My experience says “everything”!

∧

THE STORY TELLING MINISTER, or

THE VERMONT MARBLE FROM WHICH I AM A CHIP

He was called by his Chinese country parishioners, “The Shua Gu Shir Di Mushir”. [Hear EARR pronounce this name from the 1976 caseette recording she made of Grandpa’s Jokes and Stories.] This was because his usual way of preaching a sermon in the rough countrysides of North China was to tell stories, often accompanied by singing a song that would help to illustrate or expand his message. If he felt the call he also might expand even further by telling a joke. Always the ending of the meeting was filled with warm feelings, shared smiles and laughter. Somehow this method seemed to suit both the relatively uneducated peasant congregation as well as the Union Theological Seminary educated missionary—who also was my father.

His method of fathering was quite similar to his form of ministering, in that the best way for him to connect with all people was by being the real person that he was—namely a down-to-earth Vermont farm boy, in a family of 7 children (two boys and five girls), with an unbeknownst to him, amazing photographic memory. It was this photographic memory that provided his entry into the larger world of higher education, and eventually, different cultures. And in these wider world experiences his influence was vast.

Entering the Warren, Vermont Robinson clan in 1886—as the first male child—my father early in his farm family life assumed the role of eldest son with extra responsibilities: how to plow and harrow with a team of horses as well as how to feed, diaper and comfort his fast arriving siblings. His earliest vivid memory was of the birth of his sister Mabel, when he was only two years old. Another early memory was of a family buggy ride to the cemetery at the top of the hill to bury a new little sibling, when he was about four. Although it is unusual for a child this young to have such clear memory pictures, he believed that on a farm where birth and death are so closely connected, these two family events became indelibly etched on his mind. Doubtless this is true, but the course of his later life was in part determined by the fact that two school principals independently observed that he was gifted with a photographic memory.

Mr. Mathewson headed up Warren’s one-room school and when my father graduated from 8th grade, he advised my grandparents that their son could recall from memory whole pages of textbooks, and this unusual mind would be wasted if he didn’t go on to high school. The nearest high school would require that this very bright student would have to live away from home, and his parents needed him on the farm and had no money to pay board and room elsewhere. However the principal was adamant, and found a friend in the next town who could use help on his farm, and would be happy to have help in lieu of money. So my father left home at the age of 13, doing chores for his new family while he attended Waitsfield High School.

Graduating at the age of 17, didn’t mean a return to his family in Warren however, since the principal of Waitsfield high school also had observed the unusual photographic memory of this out of town student. Having himself graduated from Dartmouth College across the mountains in New Hampshire, he decided to push this already balding young man to apply there, promising that he would make sure that my father would be able to pay the costs, just as he himself had done, with various odd jobs. So my father worked his way through Dartmouth, waiting table, pressing clothes for students and faculty, and now and then in winter and early spring, collecting sap from maple tree farms and boiling it down to make maple syrup. By the time he graduated as a civil engineer, he was quite bald, and in later years, I remember his explaining his youthful shiny pate, by joking that “The best men always come out on top.”

And thus it was that my father’s career began with other people determining the course of his life, rather than his having any driving personal ambition. He himself realized this, and stated when he looked back at his long and eventful life, that he had never dreamed big dreams for himself. But when other people suggested adventures—once he had crossed from his birth town of Warren, into the next town of Waitsfield and then across the Green Mountains to Hanover, New Hampshire—it seemed easy to move across the country to teach in Hawaii, and from there to move across the Pacific to be a missionary in China. From the beginning to the end of his life, he was always unassuming, and unaware of the fact that he was uniquely gifted as a spiritual bridge builder.

A stroke cut short his life at the age of 95. Only toward the end did his mind begin to lose its clarity. Beloved by peoples of two continents, he probably never realized that the earthy Vermont farm boy, just by being his down to earth simple self, had taught those who came his way also to be themselves, not needing to hide under false finery or self made importance.

It is now some 30 years since he left this world, but his stories, jokes and songs still linger in my head, and I imagine also in the heads of the children of those Chinese peasants to whom more than half a century ago, he “told the old old story of Jesus and his love”.

The last wisdom story he gave me occurred as I was about to end my final weekend visit to his retirement home in Carmel. “Don’t forget the lantern on your bicycle” he said. Not totally in sync with his train of thought, I asked him to repeat what he had said. “Don’t forget the lantern on your bicycle.” Ah, yes, then I got it!..... His story of one cold wintry night long ago in the Chinese countryside when he was riding his bicycle from one little church to another.

It had turned dark and he had forgotten his bicycle lantern. The country roads were essentially hardened mud ruts, which without light became dangerous to maneuver at night, for an accident out in the empty countryside might be an occasion of banditry and perhaps physical harm. Fortunately, for my father—the “Shua Gu Shir De Mushir”—one of his Chinese parishioners offered to accompany him to the next church, going ahead lighting the way with the lantern on his bicycle. Now, some 60 years later, on this weekend night in Carmel, California, my old father was again back in the Chinese countryside, planning to ride to the next little mud brick church, and he remembered that he had no lantern for his bicycle. Only this time his bicycle and my car had become one. He knew I was leaving him and he wanted to be sure my journey home would be well lighted, so as to avoid accidents causing physical harm or possibly banditry.

∧

MY OLDEST BROTHER, HAROLD, or L’ENFANT TERRIBLE or

THE NATURAL HISTORY OF BI-POLAR AFFLICTION

Around 1917 my parents moved from Peking, where they had been enrolled in The Chinese Language School, to a missionary compound in the north side of Paotingfu, the capital city of Hopei, China. Not very long after they arrived in their new home, my mother’s first child was due. The only hospital in the city was in the Presbyterian missionary compound across town and the only way to reach it was by foot, by wheelbarrow or by rickshaw. The distance was perhaps 2 miles.

As every mother knows, first child labor pains send a signal to primitive nerve endings which alert the woman to the fact that something important is about to happen. As luck would have it, my father was away from home at that time and to my mother, the signal set in motion thoughts about getting to the hospital on time. The best way was to call a rickshaw, lumber her awkward body into it and tell the rickshaw puller to go as fast as he could to the Presbyterian compound. Apparently she arrived in plenty of time, for her baby proved not yet ready to greet the world. And another rickshaw was called to take my exhausted and embarrassed mother home. This unfruitful rickshaw adventure was doomed to take place once more before a third—this time successful—race across town delivered my oldest brother into the world on New Years Eve of 1918. His long-delayed trip down the birth canal marked his life-long tendency to do the unexpected rather than to follow the rules.

As the first born he was named Harold, after our father, and given a Chinese Christian name of “Kui Min”, translated as “Great Intelligence”. By our beloved Chinese cook, however he was nicknamed “Lao Cheh Tze”, meaning “Old Eggplant”, for what reason no one ever knew, but the name stuck, and by it my oldest brother was affectionately known to all our servants for as long as we lived in Paotingfu.

From the beginning Harold’s nature was difficult. His little body soon began to show that he was allergic to almost everything, and since at that time nothing was understood about how to deal with protesting little tummies and raw itchy rashes, his behavior quite naturally often was baffling and unsoothable. Our poor mother struggled without success to find clues for calming and comforting her first born son, but his inborn make-up defied all her efforts. In time when there were three children to care for, the sibling dynamics might have done her in, except for the fact that as Americans in China, patient and loving Chinese amahs were found for each child, so that our mother could return to her pre-marriage career of teaching in the local missionary school.

As the family increased in size, my oldest brother became the ringleader in creating mischief. His allergies continued to plague him, and after the birth of his little brother jealousy undoubtedly inflamed his irritable restlessness, setting up a cycle of undercover actions which he would blame on his little brother. Being three years younger, Jamie took a long time to catch on to this unfairness. And it is likely that only our observant and wise servants knew that it was “Da Gu” (Big Brother) not “Dee Dee”(Little Brother) who was the family naughty boy, or in Chinese the “tao chi di shao hai tze”.

Three years after my brother James was born, I joined the family. As the only girl, as well as the youngest child, I was able to learn from watching the interactions of my siblings, and could see that my younger brother, not knowing how to speak up for himself against the cleverness of our older brother, would be punished for what I knew he had not done. Somehow innocent little Jamie became in my parents’ unknowing eyes, the one who stirred up tumultuous family situations while Harold seemed to be the family’s “good boy”. Early on my little girl self came to admire my oldest brother for his cleverness in shucking off guilt and escaping whatever punishment was meted out. Although I often felt sorry for Jamie and would carry food to his place of banishment, I saw that Harold got the goodies for being sneaky.

As is often the case, once a role is set up within the family, that part becomes a fixed facet of the personality and is carried on throughout life. When it came time for Harold to move away from home schooling to boarding school, sure enough he became a primary practical joker within his group at the North China American School in Tungchow, outside Peking, where missionary children went when the Calvert School Method ended at 8th grade. As it happened our Paotingfu compound included another family with boys around the same ages, so that Mrs. Hubbard and my mother shared the schooling of their two rowdy pre-adolescent sons until their patience gave out, and Ward Hubbard and Harold went together off to 7th grade in NCAS [North China American School].

Except for short vacations during the school year when he would come home for a few weeks, and the long 3 month summer family vacations, I saw little of my oldest brother, until I too, at the age of 11 finally came to NCAS as a 6th grader. Ordinarily boarding school education started at 7th grade, but due to the Great Depression, many missionary families were brought back to the U.S., as a means of mission boards’ saving money. Since both my parents had been teachers in a Hawaiian boarding school prior to coming to China, they were invited to leave their work with Chinese in Paotingfu, and come to Tungchow where my father would be principal, my mother English teacher, and together, they would double as house parents for the younger boys dorm. As it happened, there were two other families with children ready for 6th grade living in Tungchow at that time, so we three 11 year old 6th graders, shared classes with the regular 7th graders.

I chose to live in the Girls Dorm with the boarding girls rather than in the “Little Boys’ Dorm” with my parents. And from this vantage, mixing with the regulars instead of living as my parents’ child, I was able to observe that my oldest brother was one of the most admired BIG boys. I could also observe that his long-term painful facial dermatitis, now scratched to oozing sores and covered by a white gauze face mask, had became a sort of stigmata badge of honor among his peers, both boys and girls.

Even today, 70-odd years later, those of us NCAS alumnae still living, speak fondly of my oldest brother “Hatcher”—the nickname he acquired back then—short for his initials: HSR. Because he was gifted with a brilliant mind as well as a quick wit, often injecting new ideas into the class discussions, his teachers also favored him, and tended to give him special duties and attentions. This was true in a different sort of way with Mr. Lund, NCAS’ Danish principal, who took a liking to Harold when he, graduating from 8th grade, moved into Wysteria Lodge the High School boys dorm, where Mr. Lund held sway.

Mr. Lund had been hired to replace the previous principal who unexpectedly had been called back to the States. No one seemed ever to quite know just why Mr. Lund had left Denmark for China. But when NCAS’ sudden vacancy arose, and a replacement was needed, the current Peking Boy Scout troupe leader appeared to be a well suited, immediately available candidate. His resume reported that in his homeland he had served both as teacher and principal in a boys boarding school, as well as having a history with the Boy Scouts of Denmark. His balding head, rosy face and heavy body that limped along with a cane, bespoke a well-mellowed middle-aged gentleman, and the fact that he spoke English with a slight accent seemed to enhance his qualifications for the roles of principal, headmaster of the high-school boys dormitory, and Boy Scout troupe leader.

Mr. Lund’s full name was James Augustus Paul Lund, but he was known only as Mr. Lund, or in formal cases J.P. Lund. He stayed at NCAS several years. Eventually his fame narrowed down to his method of disciplining “my boys”: i.e. administering a caning. According to my younger brother James, who in his time at NCAS experienced Mr. Lund’s caning for behavior such as uncombed hair, dirty neck, or unshined shoes, a regular ritual was followed. Once a week the “guilty” were lined up outside Mr. Lund’s closed door. As one boy exited, the next would enter, closing the door behind him. A short silence preceded the swishing sound of the bamboo cane and muffled words from Mr. Lund. Usually the chastened boy managed to exit dry eyed, still hearing the ritual mantra of “I cane yoou becoose I loff yoou”!

As might be predicted from earlier family years, my oldest brother was never called to stand among the boys trembling outside Mr. Lund’s closed door. Although Hatcher thought up deviltries more worthy of chastisement than simple disregard of physical appearance, he managed to become one of Mr. Lund’s fair-haired boys. In this role of specialness, he along with other favorites, would now and then be invited to share tea in Mr. Lund’s room. His devilish villainies were transmuted into knavish pranks, worthy of being mythologized in each Year Book’s history. Even away from home, my oldest brother continued to best his younger brother, by being known as one whose behavior stood out from the crowd and was admired by those in charge.

It is rumored that Mr. Lund’s famous habit of caning boys on a weekly basis, once caused one of my little girl friends to ask in a small scared voice, “Mr. Lund, do you spank girls too?” No answer to this rumored question has survived. But eventually when various mothers (including my own) decided to dig more deeply into his background, shocking facts surfaced about his previous relationships with boys in the Danish boarding school and Scout Troop, and Mr. Lund was quietly relieved of his position.

As for Harold—Kui Min, Lao Che Tze, Hatcher—my oldest brother—his life after North China American School involved coming to the U.S. for college. His outstanding grades and mind easily got him into Dartmouth, our father’s college. Here, he managed to keep a low profile, staying out of trouble. With his missionary background, he felt different from his classmates—an outsider who skated along at the top of his class but unknown as a personality. Deciding to go into medicine, in order to have a career where he could be his own boss, he applied to medical school, winning one of the three top scores for that year’s national medical school applicants. Although World War II had started, medical students were permitted to complete their schooling and internship, before being drafted into whatever service they selected. His choice was the Navy, where he served as doctor on the Landsdowne, a destroyer in the South Pacific. From letters he sent from the ship, it seemed that most hours of each day were spent drinking coffee and playing bridge. Here, at last in the midst of a war, he felt safe. He was respected as THE Doc. No longer was he a weird missionary son. Long forgotten was the awkward uncomfortable high school boy, itching to find approval, swathed in a white gauze face mask.

Harold’s career as a doctor came to an end finally in the town of Mendocino where he played the beloved and funny medicine man to all who came to his office. Now known as “Big Doc”, his patients streamed in from all over the country, ranging from highly educated wealthy retired residents to dropout hippies. At one time he enrolled in an extensive course in Chinese Medicine, so he could accept the local radio’s request to teach an on-air course in the differences between Chinese and American medicine.

He kept up to date reading all the medical journals, and as both a well-informed scientist and compassionate physician, always he was his own boss. His standard office treatment included taking plenty of time to just sit and listen to his patients’ physical, mental or family problems. Because he didn’t believe in the then popular penicillin panacea, when his patients requested a shot, he would disappear into his back dispensary, often returning with a small clear glass bottle with non-existent pills, bearing hand-written instructions to “Take one or two pills daily as needed”. If a seriously ill hospitalized patient requested to go home to die, the required release forms would be filled out and Big Doc would continue to make home visits until death parted patient from doctor. Whatever he did, it was always clear that he cared, and when possible, also had fun. Even the sickest patients, infected by his attitude, left their consultations feeling much better.

Divorced three times, he finally gave up on marriage, coming to realize that as a bachelor, life would be less complicated. Women were always falling in love with him, and although romancing different girls in town caused its own complications, eventually the girls forgave his philandering and accepted the reality that Big Doc belonged both to no one and to everyone, and especially to Life itself. At every frolicking high-wired Mendicino town fair he could be spotted dressed in a bright red clown costume, complete with fuzzy wig, red squeeze ball nose and big floppy shoes.

But as we all know life cannot be a bowl of cherries all the time. And eventually Big Doc’s merry prankster behaviors tripped up his professional behavior. Until one of the hospital nurses reported he had twice written a patient’s medication order, which if followed would have been lethal, it was not totally clear that Mendocino’s playful medicine man was in reality suffering from certifiable bi-polar disorder. The slip of his once amazing memory which might have killed the patient, caused the local medical community immediately to rescind his license, and to order him to seek psychiatric help.

Both injunctions proved to be unbearable to my much loved, outrageously iconoclastic oldest brother. Although for a short while he attempted to stay on lithium as prescribed by the consulted psychiatrist he visited several times, he claimed it made him feel logy, so he stopped taking it. But what really did him in was the humiliation of losing his license. For a time, he consulted a lawyer wise in representing medical malpractice cases. But this realistic practical man was unable to help him, knowing all too well that untreated bi-polar clients were a lost cause, and unless the Big Doc from Mendocino stayed the rest of his life on the appropriate medication, his license would never be retrieved. No longer able to practice medicine as a doctor, Harold pretty much lost interest in everything, and before many years had passed, he gave up his life-long struggle to stop scratching all those painful itches which, one form or another, had been his uninvited companion ever since coming down the birth canal in Paotingfu, China some 78 years before.

∧

JAMIE, THE GOOD AND VIRTUOUS FELLOW

He was born almost 3 years after his oldest brother, on Oct. 4, 1920. Since our father’s first name Harold had already been given away, second best was to share our dad’s middle name which was Wesley. He was given the Chinese Christian name of “Kui Dua”, sharing the first part “Kui” with his sibling, as is the Chinese custom in families—the shared “Kui” meaning “great” with the second word, “Dua” meaning “virtue”. To the oldest born Harold then, the Chinese name of “Kui Min” ascribed (in translation) “intelligence”, and to James, the second born, the Chinese name “Kui Dua” ascribed “virtue”. The old saying that virtue is its own reward, seems to fit, for although my second brother’s virtue has earned him a variety of successes, never has he managed to stand very far out from whatever his background at the time. Our beloved old cook’s pet name for the family’s little brother was “Lao Wa Gua”, or old pumpkin, and as with our cooks’ pet name for Harold, “old egg plant”, it was never known if there was any symbolic meaning. However, since boys are so highly prized in China, both boys did know that in the eyes of our magnificent and talented cook, each was just right and neither could do any wrong.

So with the birth of James Wesley—Kui Dua—Lao Wa Gua—family pet name Jamie—the Robinson family had achieved a certain status in China, now boasting two sons. Until I was born three years after Jamie, so far as I know, life in a missionary compound in Paotingfu, China, assumed a certain stability and rhythm. When I became old enough to have any memory about how it was to live in our family, what stands out about my relationship to my two brothers, is that I loved them both, but I looked up most to Harold. What I remember about Jamie when both he and Harold were present, has to do with various events in which he was bested by our oldest sibling who managed to escape every shady interaction, by placing the blame on his little brother. Although I believe both Jamie and I at some level realized this was not fair, neither of us did anything about explaining this to our parents. There were living in our compound at that time another family with boys and a girl, so that both brothers and I had companions to play with, right next door in the other grey brick two-storied missionary house.

Vaguely I remember that when I was around five and succumbed to scarlet fever, my mother and I were sequestered in an upstairs bedroom, where strange wispy dreams dragged me in and out of consciousness. We must have been there several weeks. Fortunately mother didn’t contract the illness, and eventually we both were released from the upstairs prison healthy. When finally back on my feet, I again had the run of the house, only Jamie was around, our oldest brother having gone off to boarding school.

Although Jamie and I didn’t have much playtime in common, I do remember a few events which we shared. One was of building a secret little lean-to brick and straw house where we hid a filthy hardened old block of molasses. This we had found out in the goat pen, where it was apparently useful to the goats who enjoyed licking it for its sweet taste. We stowed our amazing molasses treasure in a special space between several bricks in the little lean-to house, and periodically we would share a trip there to have a few a licks ourselves. It’s is a mystery that both of us survived such a magnificently unhealthy treat.

The second event which I clearly remember, involved Jamie, myself and our playmates, the next-door missionary brother and sister. My father was away on one of his Chinese country church visitations, and the four of us kids gathered on the little porch outside his study, which without his being present doubtless seemed a safe place to bring up our secret concerns about the differences between boys and girls. The little I recall from this titillating discussion involved wondering whether a boy’s penis could really do all the things that somehow we had, by osmosis perhaps, come to believe. I don’t remember if we solved any of our concerns, but I do remember that when suddenly my mother opened the study door onto the porch, I felt terribly guilty. As if our clandestined meeting was really an enormous transgression, against the rules of grownups.

Although today I can’t in my mind’s eye see my mother’s facial expression, I can bring up my feelings that she was nearly as terrified in her role of discoverer as were we in the role of the discovered. In those days, missionary adults colluded keeping kids in the dark about the grownup world of sexuality. I imagine my mother, realizing my father—the usual disciplinarian was gone—knew that it was up to her to devise an appropriate punishment. In this situation she needed to take on a role that was foreign to her nature. Out of familiar emotional territory, she waded into deep waters way over her previous experience. Right on the spot she devised—what seemed to me then and still does today—an inappropriate punishment: for each kid a large tablespoon of caster oil!

Now, as I think about it, I suppose for my mother, the single really unpleasant duty she had involving us kids, was to administer caster oil. So what immediately came to her mind as an unpleasant but necessary duty, when appropriate, was getting out the nasty bottle, and tablespooning it into our helplessly defiant mouths. To this day I can almost reproduce the horrible oily taste clinging to every taste bud, before being swallowed. Even once swallowed, the residual pungent stickiness clung for hours. There simply was no escape... Although on second thought, quite possibly brother Harold, with his ever tricky mind might have found one. I, being the littlest one, was never aware of his ever even having to take a dose of the dreaded stuff.

There is one final experience with Jamie of which I actually have no memory, but because it was repeated so often as part of family lore, I feel close to. This occurred one summer when due to sporadically violent Chinese war-lording near our Paotingfu compound, the mission board dispersed all families to missionary families in Taiku, South Korea. I must have been about two and a half and Jamie around 6. Being the two youngest, we probably shared a room and our parents, apparently away over night had left him in charge of his in-process-of-being-potty trained little sister. The family with whom we stayed reported hearing James muttering to himself as he led me by the hand down the dark hall to the toilet, “Elizabeth, you’re the worstest girl in the world. The very worstest girl in the whole world”!

Years went by without my catching hold of any outstanding important memories of my second brother’s presence. And when it came time for Jamie to join brother Harold in boarding school, I more or less lost contact with both of them. When, occasioned by the mission board’s financial situation in the mid 1930’s depression years, my parents were moved to Tungchow where the boarding school was located, I finally became reacquainted with them—mostly however just viewing them as two big shots in High School. From a distance I looked up to Harold, nicknamed “Hatcher”, and James affectionately among his peers called “Jamma”, and felt proud to be related to both of them. However, I admired Hatcher the most. His boisterous outrageous behavior completely overshadowed his younger brother’s good nature, good looks and considerable skill at sports. Both achieved good grades, and both played the piano well. Each had success with a variety of girls. But Hatcher, even with his painfully oozing allergic pustules hidden behind the white gauze mask, had the ability to standout from any and all crowds as someone special, even charismatic. He was one of Mr. Lund’s “my boys”, who never received a caning, while Jamma, the good and virtuous, often was among those lined up outside the closed door awaiting the weekly ritual “punishment”, for nothing more than being out of the loop with “Lund the all powerful.”

As the years went by, my two brothers continued to run side by side. They continued to compete, neck and neck, always three years apart in age, all through college and graduate school. Both went to our father’s college, Dartmouth, where they both earned Phi Beta Kappa Keys. Both chose to stay on there for medical school. Both did the first part of internship at Mary Hitchcock Hospital, also affiliated with Dartmouth. And both left New Hampshire to finish internships and residencies at Philadelphia General Hospital. Off and on during these years they even both dated the same girl! (Neither married her.) Both after training became Navy doctors. However, Harold became a real Naval doctor, shipped off to the South Pacific where he saw a few seasick sailors, a few appendicitises, and played a lot of bridge. For James whose training was completed after World War II ended, service in the Navy involved becoming one of the doctors in a Southern California naval base clinic, where the greatest excitement occurred when some Naval brass came to inspect the premises, wearing the symbolic white gloves to check on equipment, cleanliness and saluting practice.

Of course there is much much more to tell, but I find that it is infinitely harder to fill in all the years between then and now with both me and the protagonist still alive. I suppose that’s because one never knows how anything really comes out until an ending has been reached. And my second brother—James, Jamie, Jamma, Kui Dui, Lao Wa Gua—still is alive—not very well and very forgetful, but still pretty much the same person he has always been. Now he is old and crippled, but no longer does he have to compete with his older brother or anyone else. He continues to be a good and well-named, virtuous fellow.

∧

CAROL

“Actually” was her favorite word and she would say it

with a certain intonation. “ACTtully”.... proceeding

from there into some sort of outrageous statement about how she

was at that moment feeling towards her most intimate family

members—husband, children, gardener or Mexican housekeeper.

She was outspoken, easily tearful and adored jazz as well as

classical music. Often when I came by for one of our sisterly

visits, I would find her in their living room seated at one of

the two 12 foot grand pianos playing her heart out. At parties

“Actually” was her favorite word and she would say it

with a certain intonation. “ACTtully”.... proceeding

from there into some sort of outrageous statement about how she

was at that moment feeling towards her most intimate family

members—husband, children, gardener or Mexican housekeeper.

She was outspoken, easily tearful and adored jazz as well as

classical music. Often when I came by for one of our sisterly

visits, I would find her in their living room seated at one of

the two 12 foot grand pianos playing her heart out. At parties

she played for applause and fun. Alone at home she played to

unburden her heart. For her the world as well as our individual

human lives operated irrationally and deserved tender pity, tears

and forgiveness.

she played for applause and fun. Alone at home she played to

unburden her heart. For her the world as well as our individual

human lives operated irrationally and deserved tender pity, tears

and forgiveness.

Her feeling response to everything was immediate and real, and

because this was so totally opposite from what my upbringing had

provided me, I was fascinated and emotionally released by her (to

me at first shockingly direct) feeling expressions. We met when

we were both in our mid thirties, I already with three kids and

she still without any. Carol became my best friend in the early

1950s, in part because I was more grounded in the doctors’

wives social world she was just entering, while she offered me

new learnings about the power of being comfortable with the inner

world of honest emotional realities.

Her feeling response to everything was immediate and real, and

because this was so totally opposite from what my upbringing had

provided me, I was fascinated and emotionally released by her (to

me at first shockingly direct) feeling expressions. We met when

we were both in our mid thirties, I already with three kids and

she still without any. Carol became my best friend in the early

1950s, in part because I was more grounded in the doctors’

wives social world she was just entering, while she offered me

new learnings about the power of being comfortable with the inner

world of honest emotional realities.

“NUMBER ONE Confidant” she used to call me as our woman-to-woman relationship blossomed over the many years we both were members of the San Mateo Medical Society. Eventually she had three children, her firstborn son and my last son, born three months apart, became best friends. Today, 50 years later and 3,000 miles apart they still are.

Carol died about six years ago and I still acutely mourn her loss whenever something really sad or awfully funny happens. I find myself silently mouthing words to her when events in our children’s lives come to fruition, events she saw the beginnings of all those years ago. I sometimes wonder if she isn’t up there looking down on our increasingly complicated world, alternately weeping and laughing over how ridiculous we human beings behave. Her gifts to me were life changing and beyond expression. She knew she was my dear friend, but I doubt she ever guessed she was also my great teacher.

∧

HOW LITTLE WE KNOW—AS TIME GOES BY

We had spent many hours with a lawyer. My husband had moved in and out again several times. Finally the divorce was complete...At first the house seemed relaxed for both the kids and me. We began to get used to the lack of silently awaited outbursts of anger and decreased tension.